‘Video Nasty’ is a broad term used to describe the moral panic relating to a number of movies banned for featuring supposedly excessive violence, and the distribution of these movies on video tapes in the UK in the 1980s. The main concern would come from more conservative organisations and groups such as the government and much of the press at the time in the UK. Part of the public debate spawned by the moral panic would debate the effect of these movies on children, even if just from seeing the sometimes explicit covers in a video store.

When home video came into popularity in the 70s there was no process for films to be classified or censored, unlike those released for cinemas, which were evaluated by the British Board of Film Censors. The United Kingdom had quickly become a country with one of the highest number of video recorders in the world. There were concerns within the film industry regarding pirating of videos, which allowed for cheap, independent films to become popular in this format, with horror being a leading genre.

A Brief History of the Video Nasty:

In 1982, Video Instant Picture Company (VIPCO) placed full page advertisements for The Driller Killer (1979) in numerous magazines, which depicted the films explicit cover, and would result in many complaints to the Advertising Standards Agency. Mere months after this controversy, the distributors of Cannibal Holocaust (1980) wrote anonymously to Mary Whitehouse of the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association (NVLA) in order to drive further publicity for their movie, but this would lead to a public campaign on the so-called “video nasty”’ led by Whitehouse. Whitehouse had previously made a name for herself as a campaigner against sex and violence in the media.

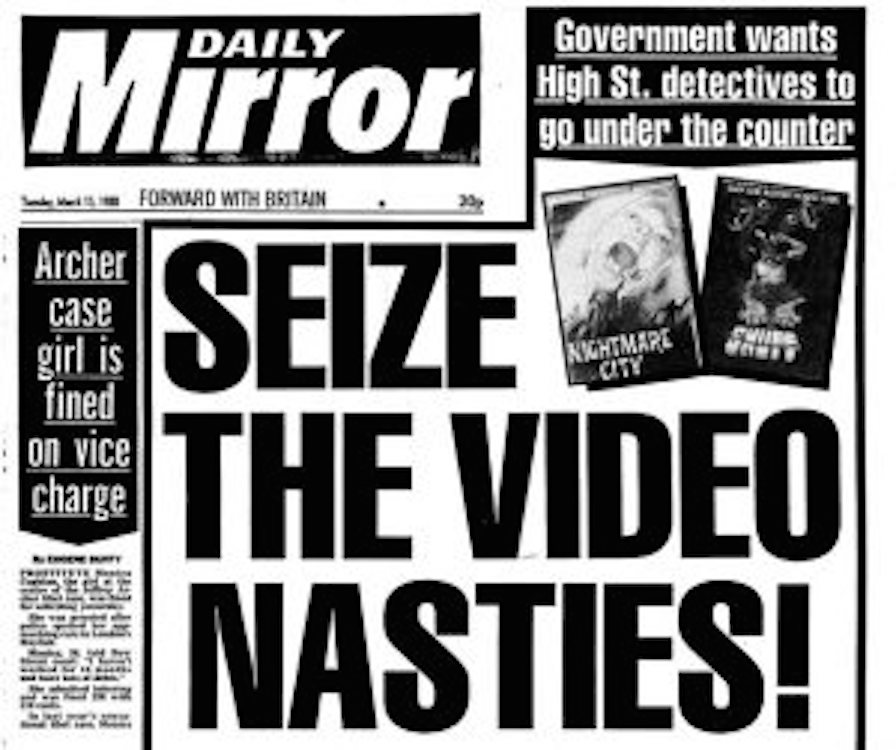

As is often the case with violent media throughout history, the media and government institutions began to blame the rising real-life crime amongst youths on these movies and the effect they were supposedly having on young people. Following further publicity and panic generated by popular and influential newspapers on the topic, a bill would be introduced in the House of Commons by Conservative MP Graham Bright, at the suggestion of the NVLA in order to combat this supposed issue. This Private Member’s Bill introduced in 1983 would later become the Video Recordings Act 1984, and came into effect on September 1st 1985.

The Video Recordings Act 1984 states that commercial video recordings for sale or rent within the UK must carry a classification agreed upon by the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). The selling or renting of unclassified movies, or movies rated 15 or 18 to children under those ages would become prosecutable offences under this Act.

While the main target of the Act was to curb the low-budget horror films primarily deemed too extreme, there were some big name movies such as The Exorcist (1973), which were affected too. The Exorcist was released in 1981, but was not submitted for classification and as a result was removed from shelves in 1986. Claims, since proven to be speculative or media fabrications, that Child’s Play 3 (1991) influenced the perpetrators of the murder of James Bulger further prompted restrictions in the mid 1990s.

David Alton, the MP for the Liberal Democrats at the time, would lead the campaign against video nasties around the time of the Bulger murder, reportedly deeply concerned by these reports that the nasties had influenced the killers. After years of panic created by the press, the public had become convinced of the same thing Alton had, and he had received letters upon letters demanding action from the terrified public.

Restrictions would begin to loosen following the departure of James Ferman from the BBFC, and public consultation in the late 90s. The Exorcist was granted an uncut 18 rating in February 1999 and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre would follow suit in August of the same year, with many other ‘nasties’ also being re-evaluated in the early 2000s.

British Newspapers and Their Influence:

The first national press story regarding the dangers of home video came from the Mail in May of 1982 under the headline of “The Secret Video Show”. The article warns that children will now have access to “the worst excesses of cinema sex and violence”.

The Sunday Times newspaper was the first to use the term “video nasties” in the national press, under the article headlined “How High Street Horror is Invading the Home”. The article would go on to mention that these videos were “rapidly replacing sexual pornography as the video trade’s biggest moneyspinner”.

Many articles would be published by the Daily Mail with headlines such as “We Must Protect Our Children Now” and “The Rape of Our Children’s Minds”. The latter article would compare the so-called threat of these movies to Nazism with the following: “Britain fought the last World War against Hitler to defeat a creed so perverted that it spawned such horrors in awful truth. Now Britain allows our children to be nurtured on these perverted horrors and on any permutation of them under the guise of ‘entertainment’”.

In the UK, the press have often been heavily involved in the creation and continuation of moral panics, and here is no different. The constant tirade of sensationalist language used to describe these movies and those who distribute them is clearly at fault, particularly in the case of the Mail, of blowing up this issue to the point of gaining political attention. Reporting of video nasties in the Times would far precede any public outrage or political discussion, and would definitely be considered a key actor in the development of the moral panic.

Video Nasties these days are often movies to be celebrated, with many of them being some of the most influential and important genre movies to ever exist. It is insane to think of some of these films as being thought of the way they were back then, and while there is still precedent for modern moral panics regarding the correlation of real life violence and violent media, it thankfully is not to the extent of the video nasty moral panic.